Definition

In short, it’s Security Orchestration, Automation And Response.

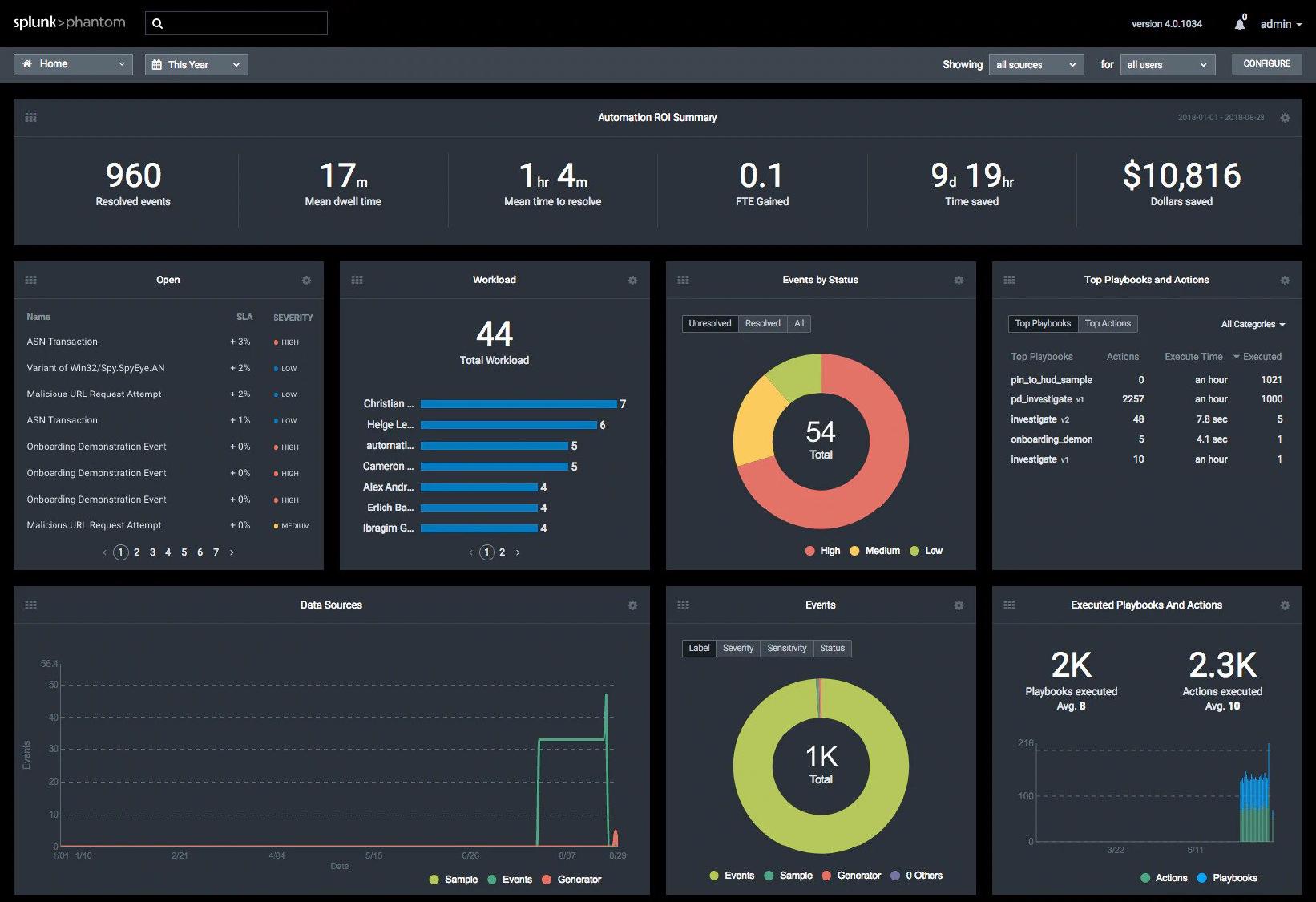

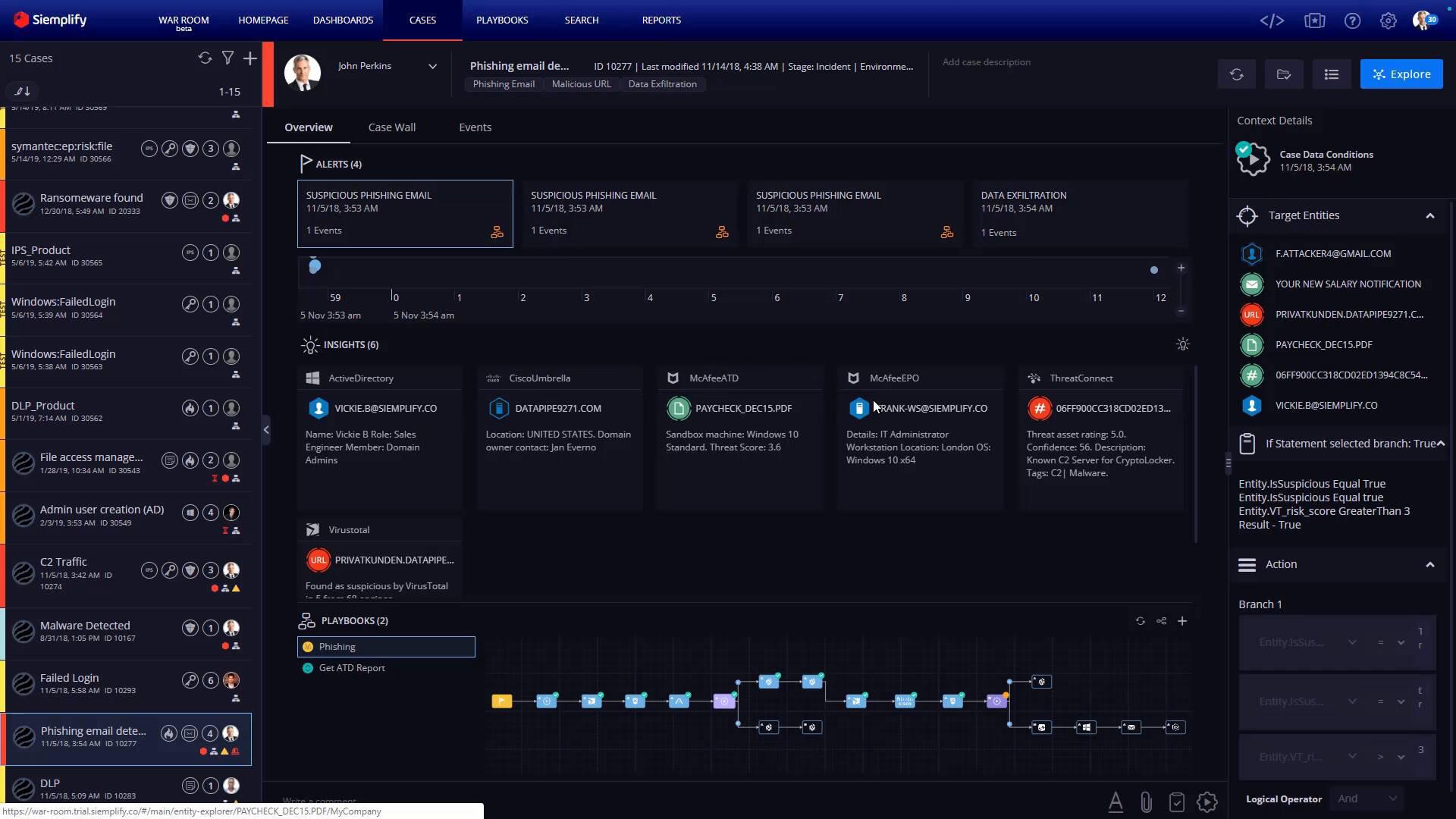

SOAR refers to technologies that enable organizations to collect inputs monitored by the security operations team. For example, alerts from the SIEM system and other security technologies — where incident analysis and triage can be performed by leveraging a combination of human and machine power — help define, prioritize and drive standardized incident response activities. SOAR tools allow an organization to define incident analysis and response procedures in a digital workflow format.

Explanation

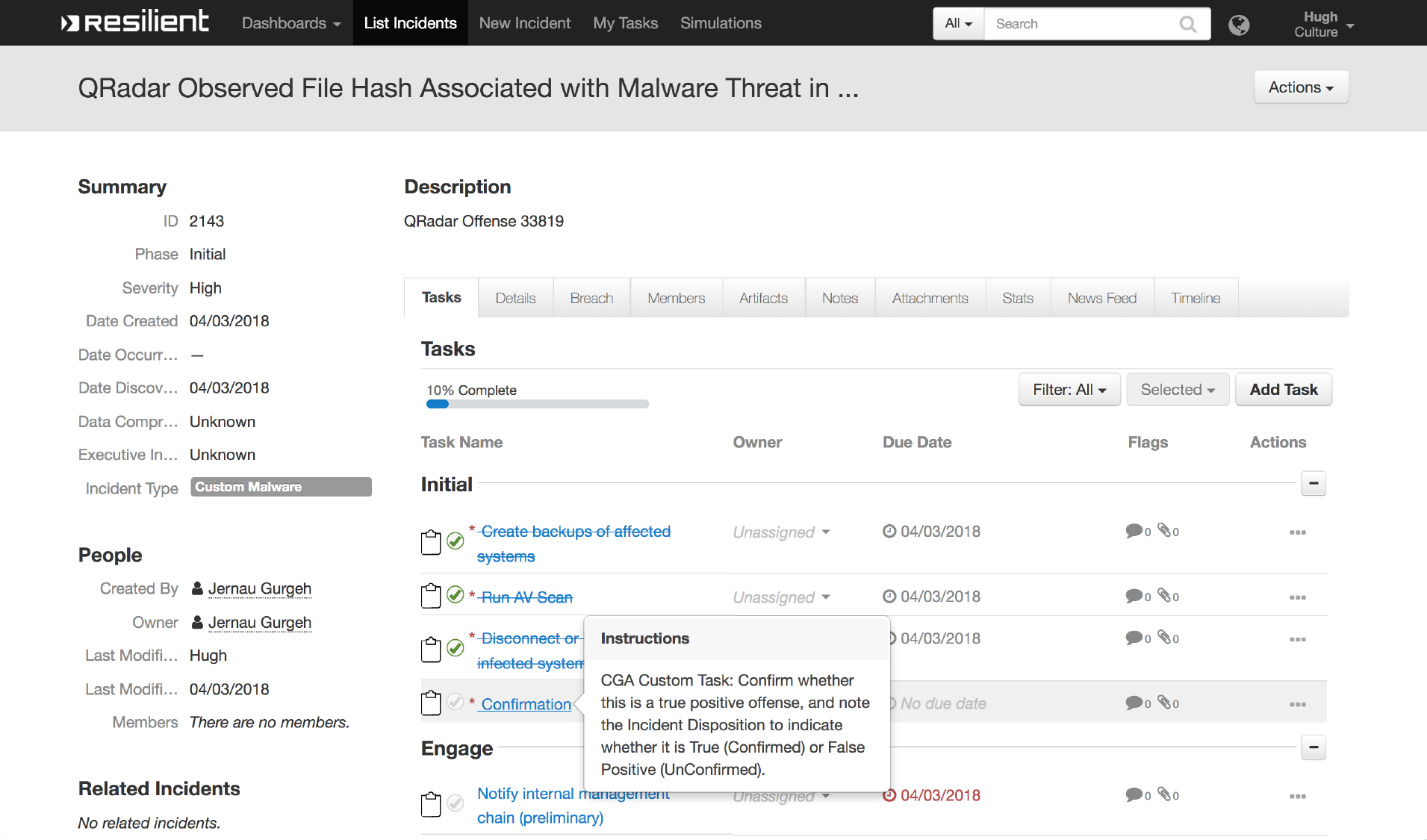

On the surface, SOAR is yet another ticket tracking system. Imagine any ticket tracking system you were using in the past. It probably had ways to create, prioritize and filter tickets. It also could change assigned persons, keep attachments and so on.

What makes SOAR unique is the addition of several ideas.

The first idea is to rely on automation as much as possible. For example, the system can:

- automatically prioritize the ticket when it’s created and assign it to a proper person

- unzip and analyze a file when somebody attaches it in ticket’s comments

- create a ticket automatically when the system observes some change in external systems

- close a ticket automatically when it’s clear there’s nothing left to do

- call APIs of dozens of external systems when a ticket changes to a particular state. Also, notify interested people. This is called orchestration.

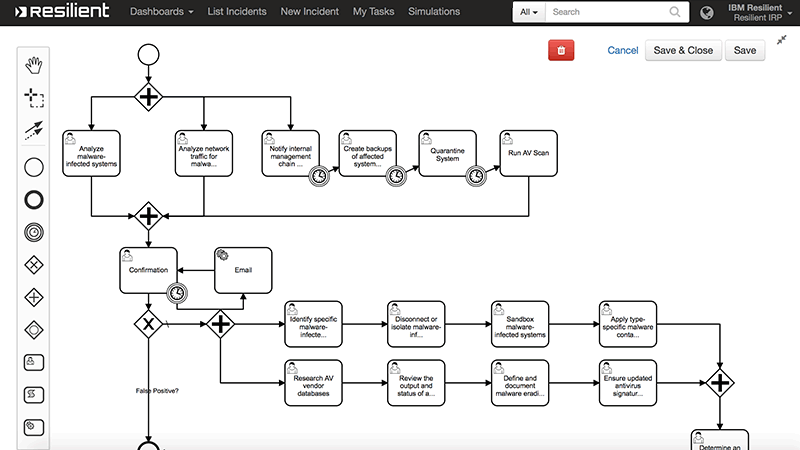

This is typically implemented this using rules and actions. Rules use a special language. The language allows to describe a condition for any event happening in the system. When the condition is satisfied, rule starts a pre-programmed set of actions. For example, the condition can be “new ticket is created”, actions can be “prioritize the ticket” + “assign it to a person”. Rules and actions form playbooks, which can be replayed for each new event.

The second idea is to put the system in the security domain.

That means tickets are actually security incidents. The system is aware of the existence of IPs, malware, threats, vulnerabilities, and other entities common in cybersecurity. The system can manipulate those entities to enrich information in the incident and correlate it with other incidents. For example, the system can check whois information for an IP mentioned in the incident and then mark this IP as untrusted.

Security incidents require a response. During response, the system can change firewall rules, remove malicious files, and so on. A response can be very simple (if the incident was false positive) or very complex (if the system needs to orchestrate dozens of systems and several departments of the company).

All of this is done to simplify life of people in security operation centers. And also life of people who pay for company’s security.