Useful read. I no longer believe those who talk about things selling “below their real value” or about how terrible it is for the United States to be “a debtor nation”. I’m skeptic about government programs to make this or that “affordable”. Same skepticism goes for statements and statistics about “the rich” and “the poor”. Same with notion of “greed” of capitalists. It’s not mysterious why so many places with rent control laws also have housing shortages.

Writing is mediocre, ideas are good. First chapters are especially terrible, I had a feeling that there was no editing. Most of the examples are repetitive, it was pretty annoying. I wish it was more straight (maybe even cynical). But it’s written in a simple language, that’s a plus.

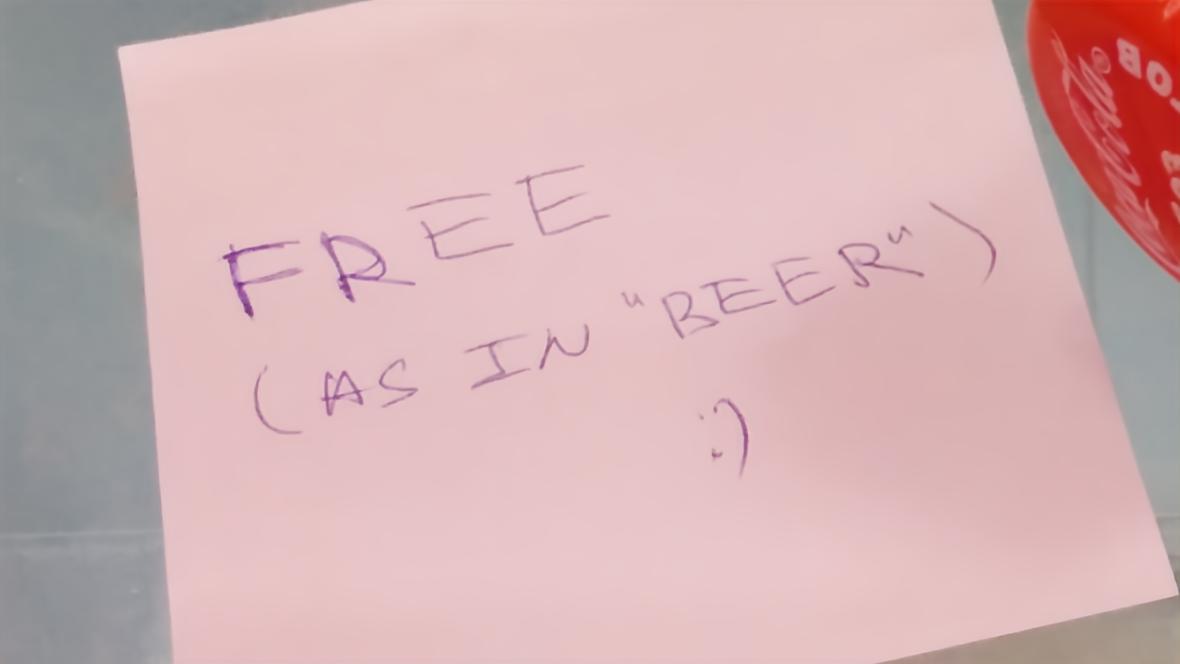

Resources tend to flow to their most valued uses.

In China, government controls were relaxed in particular economic sectors and in particular geographic regions during the reforms of the 1980s, leading to stunning economic contrasts within the same country, as well as rapid economic growth overall. In 1978, less than 10 percent of China’s agricultural output was sold in open markets but, by 1990, 80 percent was. The net result was more food and a greater variety of food available to city dwellers in China and a rise in farmer’s income by more than 50 percent within a few years.

In a price-coordinated economy, employees and creditors insist on being paid, regardless of whether the managers and owners have made mistakes. This means that businesses can make only so many mistakes for so long before they have to either stop or get stopped-whether by an inability to get the labor and supplies they need or by bankruptcy. In a feudal economy or a socialist economy, leaders can continue to make the same mistakes indefinitely. The consequences are paid by others in the form of a standard of living lower than it would be if there were greater efficiency in the use of scarce resources.

When people project that there will be a shortage of engineers or teachers or housing in the years ahead, they usually either ignore prices or implicitly assume that there will be a shortage at today’s prices. But shortages are precisely what cause prices to rise.

At higher prices, it may be no harder to fill vacancies for engineers or teachers than today and no harder to find housing.

When a large employer goes bankrupt in a small community, or simply moves away to another state or country, many of the business’ former employees may decide to move away themselves - and when their numerous homes go on sale in the same small area at the same time, the prices of those houses are likely to be driven down by competition. But this does not mean that they are selling for less than their ”real” value. The value of living in this particular community has simply declined with the decline of job opportunities, and housing prices reflect that underlying fact. The new and lower prices reflect the new reality as well as the previous prices reflected the previous reality.

To understand the effects of price control, it is necessary to understand how prices rise and fall in a free market. There is nothing esoteric about it, but it is important to be very clear about what happens. Prices rise because the amount demanded exceeds the amount supplied at existing prices. Prices fall because the amount supplied exceeds the amount demanded at existing prices.

The first case is called a “shortage” and the second is called a “surplus”-but both depend on existing prices.

When there is a “shortage” of a product, there is not necessarily any less of it, either absolutely or relative to the number of consumers. During and immediately after the Second World War, for example, there was a very serious housing shortage in the United States, even though the population and the housing supply had both increased about 10 percent from their prewar levels and there was no shortage when the war began.

In other words, even though the ratio between housing and people had not changed, nevertheless many Americans looking for an apartment during this period had to spend weeks or months in an often vain search for a place to live, or else resorted to bribes to get landlords to move them to the top of waiting lists. Meanwhile, they doubled up with relatives, slept in garages or used other makeshift living arrangements.

Although there was no less housing space per person than before, the shortage was very real at existing prices, which were kept artificially lower than they would have been because of rent control laws that had been passed during the war.

The number of abandoned buildings taken over by the New York City government runs into the thousands. It has been estimated that there are at least four times as many abandoned housing units in New York City as there are homeless people on the streets there. Such inefficiency in the allocation of resources means that people are sleeping outdoors on the pavement on cold winter nights-some dying of exposure-while the means of housing them already exist, but are not being used because of laws designed to make housing ”affordable".

How to get rid of all this surplus farm produce was a continuing question for which all sorts of answers were devised over the years. In theory, the surpluses built up during bumper crop years could be sold in the marketplace during years when there were smaller crops, without driving the price down below the price support level. In practice, however, this provided little relief. Often the surplus food was either sold to other countries at lower prices than the American government had paid for it or it was given away overseas to meet various food emergencies that arose in various countries from time to time.

The cost of agricultural price support programs to the taxpayers reached a peak of more than $16 billion in 1987, before changes in the laws and policies cut that in half by 1991. However, this does not count the additional billions paid by the public in the form of artificially higher food prices. For example, during the mid-1980s, when the price of sugar on the world market was four cents a pound, the wholesale price within the United States was 20 cents a pound.

Although the original rationale for such programs was to save the family farm, in practice more of the money went to big agricultural corporations, some of which received millions of dollars each, while the average farm received only a few hundred dollars.

Since this was a local food shortage, the ordinary effect of supply and demand would have been to cause local prices to rise, attracting more food into the area. Price controls prevented that.

Nor was this perverse reaction peculiar to Italy. The same thing has happened in many countries and in many centuries. In eighteenth-century India, for example, a local famine in Bengal brought a government crackdown on food dealers and speculators, imposing price controls on rice, leading to widespread deaths by starvation.

While rising prices are likely to reflect changes in supply and demand, people ignorant of economics may attribute the rises to “greed.” Such an intentional explanation raises more questions than it answers. Why does greed vary so much from one time to another or from one place to another?

In the Los Angeles basin, for example, homes near the ocean sell for much higher prices than similar homes located in the smog-chocked interior. Does this mean that fresh air promotes greed, while smog makes home sellers more reasonable? To say that prices are due to greed is to imply that sellers can set prices by an act of will. If so, no company would ever go bankrupt, since it could simply raise its prices to cover whatever its costs happened to be.

Incentives matter because most people will do more for their own benefit than for the benefit of others. Incentives link the two concerns together. A waitress brings food to your table, not because of your hunger, but because her salary and tips depend on it. Giant corporations hire people to find out what their customers want, not because of altruism, but because they know that this is the way to make a profit and avoid losses. Producing things that people don’t want is a road that leads ultimately to the bankruptcy court.

Prices are important because they convey information in the form of incentives. Producers cannot read consumers’ minds but, when automobile manufacturers find it harder to sell station wagons at prices that cover their cost of production and easier to sell sports utility vehicles at cost-covering prices, that is all that the automobile manufacturers need to know in order to decide what to produce.

Even something as simple as an apple is not easy to define because apples differ in size, freshness, and appearance, quite aside from the different varieties of apples. In a free market, those apples most in demand for whatever reason-are likely to have higher prices and those least in demand lower prices. Produce stores and supermarkets spend time (and hence money) sorting out different kinds and qualities of apples, throwing away those that fall below a certain quality that their respective customers demand.

Under price control, however, the amount of apples demanded at an artificially low price exceeds the amount supplied, so there is no need to spend so much time and money sorting out apples, as they will all be sold anyway. Some apples that would ordinarily be thrown away under free market conditions may, under price control, be kept for sale to those people who arrive after all the good apples have been sold. As with apartments under rent control, there is no need to maintain high quality when everything will sell anyway during a shortage.

One of the incidental benefits of competing and sharing through prices is that different people are not as likely to think of themselves as rivals, nor to develop the kinds of hostility that rivalry can breed.

For example, much the same labor and construction material needed to build a Protestant church could be used to build a Catholic church. But, if a Protestant congregation is raising money to build a church for themselves, they are likely to be preoccupied with how much money they can raise and how much is needed for the kind of church they want. Construction prices may cause them to scale back some of their more elaborate plans to fit within what they can afford. But they are unlikely to blame Catholics, even though the competition of Catholics for the same construction materials makes their prices higher than otherwise.

If, instead, the government were in the business of building churches and presenting them to different groups, Protestants and Catholics would be explicit rivals for this largess and neither would have any financial incentive to cut back on their building plans to accommodate the other. Instead, each would have an incentive to make the case, as strongly as possible, for the full extent of their desires and to resent any suggestion that they scale back their plans. The inherent scarcity of materials and labor would still limit what could be built, but that limit would now be imposed politically and seen by each as due to the rivalry of the other. The Constitution of the United States of course prevents the government from building churches for different groups, no doubt to prevent just such political rivalries and the bitterness, and sometimes bloodshed, to which such rivalries have led in other countries.

Prices are like thermometer readings - and a patient with a fever is not going to be helped by plunging the thermometer into ice water to lower the reading. On the contrary, if we were to take the new readings seriously and imagine that the patient’s fever was over, the dangers would be even greater, now that the underlying reality was being ignored.

Lower costs reflected in lower prices is what made A & P the world’s leading retail chain in the first half of the twentieth century. And lower costs reflected in lower prices is what enabled other supermarket chains to take A & P’s customers away in the second half of the twentieth century. While A & P succeeded in one era and failed in another, what is more important is that the economy as a whole succeeded in both eras in getting its groceries at the lowest prices possible at the time-from whichever company happened to have the lowest prices.

No economic system can depend on the continuing wisdom of its existing leaders. A price-coordinated economy with competition in the marketplace does not have to, because those leaders can be forced to change course - or be replaced-whether because of red ink, irate stockholders, outside investors ready to take over, or because of a bankruptcy court. Given such economic pressures, it is hardly surprising that economies under the thumbs of kings or commissars have seldom matched the track record of capitalist economies.

People often refer to an enterprise system as a profit system. This is a great mistake. It is a profit and loss system, and the loss, in my opinion, is more important than the profit part. The crucial difference is not in what ventures are undertaken. The crucial difference is in what ventures are continued and which ones are abandoned. The crucial requirement for maintaining growth and progress is that successful experiments be continued and unsuccessful experiments be terminated.

In short, while capitalism has a visible cost-profit-that does not exist under socialism, socialism has an invisible cost-inefficiency-that gets weeded out by losses and bankruptcy under capitalism. The fact that most goods are available more cheaply in a capitalist economy implies that profit is less costly than inefficiency. Put differently, profit is a price paid for efficiency.

When most people are asked how high they think the average rate of profit is, they usually suggest some number much higher than the actual rate of profit. From 1978 through 1998, American corporate profit rates fluctuated between a low of just above 6 percent to a high of about 13 percent. As a percentage of national income, corporate profits after taxes never exceeded 9 percent and was often below 6 percent over a thirty-year period ending in 1998. However, it is not just the numerical rate of profit that most people misconceive. Many misconceive its whole role in a price-coordinated economy, which is to serve as incentives - and it plays that role wherever its fluctuations take it. Moreover, some people have no idea that there are vast differences between profits on sale and profits on investments.

Despite superficially appealing phrases about “eliminating the middleman,” middlemen continue to exist because they can do their phase of the operation more efficiently than others. It should hardly be surprising that people who specialize in one phase can do that phase better than others.

Just over half the bricks in the U.S.S.R. were produced by enterprises that were not set up for that purpose, but which made their own bricks in order to build whatever needed building to house their main economic activity. That was because these Soviet enterprises could not rely on deliveries from the Ministry of Construction Materials, which had no financial incentives to be reliable in delivering bricks on time or of the quality required.

One of the continuing problems of the airline industry-airport congestion occurs because landing fees have not been deregulated. Instead of being determined by supply and demand for landing rights at airports, landing fees are determined by arbitrary formulas which allow small private planes to use a scarce resource at less than its value to jumbo jets carrying hundreds of passengers. The predictable net result is that small private planes carrying a handful of people are able to land at overcrowded major airports when they could just as easily land at smaller airports where they would not either delay vastly larger numbers of other passengers or preclude the scheduling of more flights in bigger planes.

A 100 percent monopoly of Valencia oranges would mean little if people were free to buy navel oranges, tangerines, and other similar fruit. In a sense, every company that sells brand-name merchandise has a monopoly of that particular merchandise. But a monopoly of Canon cameras means little when photographers are free to buy Nikon, Minolta, Pentax, and other cameras.

For example, if the stock is worth $80 a share under inefficient management, outside investors can start buying it up at $90 a share until they have a controlling interest in the corporation. After using that control to fire existing managers and replace them with a more efficient management team, the value of the stock might rise to $150 a share. While this profit is what motivates the investors, from the standpoint of the economy as a whole, what matters is that such a rise in stock prices usually means that either the business is now serving more customers, or offering them better quality or lower prices, or is operating at lower cost - or some combination of these things.

As automobile ownership and suburbanization spread across the country, so did McDonald’s. By 1988, half of McDonald’s sales were made at drive-through windows, which were capable of handling a car every 25 seconds, or well over a hundred per hour. As with the supermarkets, this represented extremely low costs of selling, enabling prices to be kept down to levels that were highly competitive. Drive-through restaurants in general require far less land per customer served than does a sit-down restaurant. This of course lowers the cost of doing business.

As a scarce resource, knowledge can be bought and sold in various ways in a market economy. The hiring of agents is essentially the purchase of the agent’s knowledge to guide one’s own decisions.

Let’s go back to a basic principle of economics: The same physical object does not necessarily have the same value to different people. This applies to an author’s manuscript as well as to a house, a painting or an autograph from a rock star. What a literary agent knows is where a particular manuscript is likely to have its greatest value.

The efficient allocation of scarce resources which have alternative uses means that some must lose their ability to use those resources, in order that others can gain the ability to use them. Smith-Corona had to be prevented from using scarce resources, including both materials and labor, to make typewriters, when those resources could be used to produce computers that the public wanted more. Nor was this a matter of anyone’s fault. No matter how fine the typewriters made by Smith-Corona and or how skilled and conscientious its employees, typewriters were no longer what the public wanted after they had the option to achieve the same end result-and more-with computers.

Fortunately, since we know from Chapter 2 that there is no such thing as ”real” worth, we can save all the energy that others put into such unanswerable questions. Instead, we can ask a more down-to-earth question: What determines how much people get paid for their work? To this question there is a very down-to-earth answer: Supply and Demand. However, that is just the beginning. Why does supply and demand cause one individual to earn more than another?

If one company can manufacture widgets for $10 each and sell them for $12, making $2 gross profit on each, anybody who can manufacture them for $9 dollars each will be able to make more gross profit, whether by selling them for the same $12 and having more gross profit left over or by selling the same product for $11 and making more gross profit by taking away some of their competitor’s customers with lower prices. In either case, they earn their money by satisfying customers at lower costs of production. What this means from the standpoint of the economy as a whole is that they are using fewer of society’s resources to get the same job done.

When a freight train comes into a railroad yard or onto a siding, workers are needed to unload it. When a freight train arrives in the middle of the night, it can either be unloaded then and there, so that the train can proceed on its way, or the boxcars can be left on a siding until the workers come to work the next morning. In a country where such capital as railroad box cars are very scarce and labor is plentiful, it makes sense to have the workers available around the clock, so that they can immediately unload box cars and this very scarce resource does not remain idle. But, in a country that is rich in capital, it may often be better to let box cars sit idle on a siding, waiting to be unloaded, rather than to have expensive workers sitting around idle waiting for the next train to arrive.

It is not just a question about these particular workers’ paychecks or this particular railroad company’s expenses. From the standpoint of the economy as a whole, the more fundamental question is: What are the alternative uses of these workers’ time and the alternative uses of the railroad boxcars? In other words, it is not just a question of money.

Job security policies save the jobs of existing workers, but at the cost of reducing the flexibility and efficiency of the economy as a whole, thereby inhibiting the creation of new jobs for other workers. Because job security laws make it risky to hire new workers, existing employees may be worked overtime instead or capital may be substituted for labor, such as using huge busses instead of hiring more drivers for regular-sized busses. However it is done, increased substitution of capital for labor leaves other workers unemployed. For the working population as a whole, this is no net increase in job security. It is a concentration of the insecurity on those who happen to be on the outside looking in.

It has sometimes seemed especially galling that corporate executives who got rid of thousands of workers were rewarded by pay increases for themselves. However, it is worth considering the consequences of the situation in government, where executives are likely to be rewarded according to how many people they supervise and how large a budget they administer. These different situations create opposite incentives-to get as much work done with as few people and resources as possible in private industry and with as many people and resources as available in government. This is one reason why it often costs much less for private companies to perform the same tasks as a government agency performs. The public pays the costs, whether as consumers or as taxpayers.

Because the government does not hire surplus labor the way it buys surplus agricultural output, the labor surplus takes the form of unemployment, which tends to be higher under minimum wage laws than in a free market.

As in other cases, a “surplus” is a price phenomenon, just as “shortages” are. Unemployed workers are not surplus in the sense of being useless or in the sense that there is no work around that needs doing. Most of these workers are perfectly capable of producing goods and services, even if not to the same extent as more skilled workers. The unemployed are made idle by wage rates artificially set above the level of their productivity. By being idled in their youth, they are of course prevented from acquiring the job skills and experience which could make them more productive and higher earners later on.

This was part of a more general trend among industrial workers in the United States. The United Steelworkers of America was another large and highly successful union in getting high pay and other benefits for its members. But here too the number of jobs in the industry declined by more than 200,000 in a decade, while the steel companies invested $65 million in machinery that replaced these workers, and while the towns where steel production was concentrated were economically devastated.

The once common belief that unions were a blessing and a necessity for workers was now increasingly mixed with skepticism about the unions’ role in the economic declines and reduced employment in many industries. Faced with the prospect of seeing some employers going out of business or having to drastically reduce employment, some unions were forced into ”give-backs” that is, relinquishing various wages and benefits they had obtained for their members. Painful as this was, many unions concluded that it was the only way to save members’ jobs.

Where the consumers do not like what is being produced, the investment should not pay off. When people insist on specializing in a field for which there is little demand, their investment has been a waste of scarce resources that could have produced something that others wanted. The low pay and sparse employment opportunities in that field are a compelling signal to them - and to others coming after them-to stop making such investments.

What is being saved and invested in the present are not the goods and services that will be used in the future, but the capacity to produce those things in the future.

One of the ways of dealing with this uncertainty is to prepare alternative courses of action. These may be in the form of contingency plans or in the form of material goods stored to cover a variety of possibilities.

In short, inventory is a substitute for knowledge. If a soldier going into battle knew that he would fire exactly 36 bullets in combat, he would not need to weigh himself down with more bullets than that or with a variety of first aid and other items that he would never use. Only his lack of knowledge makes it prudent for him to carry such an inventory.

Speculation is another way of dealing with risks and uncertainties.

Economic speculation is another way of allocating scarce resources-in this case, knowledge. Neither the speculator nor the farmer knows what the prices will be when the crop is harvested. But the speculator happens to have more knowledge of markets and of economic and statistical analysis than the farmer, just as the farmer has more knowledge of how to grow the crop. My commodity speculator friend admitted that he had never actually seen a soybean and had no idea what they looked like, although he had probably bought and sold millions of dollars worth of them over the years. He simply transferred ownership of his soybeans on paper to soybean buyers at harvest time, without ever taking physical possession of them from the farmer. He was not really in the soybean business, he was in the risk management business.

As more and more of the known reserves of oil get used up, the present value of the remaining oil begins to rise and once more exploration for additional oil becomes profitable. But, as of any given time, it never pays to discover all the oil that exists in the ground or under the sea-or more than a minute fraction of that oil. What does pay is for people to write hysterical predictions that we are running out of natural resources. It pays not only in book sales and television ratings, but also in political power and in personal notoriety.

If you are a venture capitalist with $50,000 to invest in similar ventures, then you can buy $5,000 worth of stock in ten such enterprises. If the odds are 50-50 on each, then you should expect five of the ten to pay off ten-fold, while you lose $25,000 on the others that go bankrupt. Subtracting that $25,000 from the $250,000 you get from your stock in five that succeed, you still have a phenomenal return of $225,000 on an investment of $50,000. Even if you are unlucky and only two of the ten pay off, you still come out ahead, with $40,000 in losses on the eight that fail and $100,000 on the two that succeed. You get back $60,000 from the $50,000 you invested. That is a 20 percent return on your investment if you get your money back in a year and, of course, correspondingly less if it takes several years for the ventures to pay off.

Now look at the same transaction from the standpoint of the entrepreneur who is trying to raise money for his venture. Knowing that bonds would be unattractive to investors and that a bank would be reluctant to lend to him for the same reasons, he would almost certainly try to raise money by selling stocks instead. At the other end of the risk spectrum, consider a public utility that supplies something the public always needs, such as water or electricity. There is very little risk involved in putting money into such an enterprise, so the utility can issue and sell bonds, without having to pay the higher amounts that investors would earn on stocks.

The illusion of investment is maintained by giving the Social Security trust fund government bonds in exchange for the money that is taken from it and spent on current government programs. But these bonds represent no tangible assets. They are simply promises to pay money collected from future taxpayers. The country as a whole is not one dime richer because these bonds were printed, so there is no analogy with private investments which create apartment complexes, clothing factories, or automobile plants, whose productions and sales will provide the real income needed by a retired generation whose premiums built these things.

Politics and economics differ radically in the way they deal with time. For example, when it becomes clear that the fares being charged on municipal buses are too low to permit these buses to be replaced as they wear out, the logical economic conclusion for the long run is to raise the fares. Politically, however, a candidate who opposes the fare increase as ”unjustified” may gain the votes of bus riders at the next election. Moreover, since all the buses are not going to wear out immediately, the consequences of holding down the fare will not appear all at once but will be spread out over time. It may be some years before enough buses start breaking down and wearing out, without adequate replacements, for the bus riders to notice that there now seem to be longer waits between buses and they do not arrive on schedule as often as they used to.

By the time the municipal transit system gets so bad that many people begin moving out of the city, taking the taxes they pay with them, so much time may have elapsed since the political fare controversy that few people see any connection. Meanwhile, the politician who won a municipal election by assuming the role of champion of the bus riders may now have moved on up to statewide office or even national office on the basis of his popularity. As a declining tax base causes deteriorating city services and neglected infrastructure, the erstwhile hero of the bus riders may even be able to boast that things were never this bad when he was a city official, and blame the current problems on the failings of his successors.

If a private bus company’s management decided to keep fares too low to maintain and replace its buses as they wore out, or decided to pay themselves higher executive salaries instead of setting aside funds for the maintenance of their bus fleet, 99 percent of the public might still be unaware of this or its long-run consequences. But among the other one percent who would be far more likely to be aware would be financial institutions that owned stock in the bus company, or were considering buying that stock or lending money to the bus company. For these investors, potential investors, or lenders examining financial records, the company’s present value would be seen as reduced, long before the first bus wore out.

Money is equivalent to wealth for an individual only because other individuals will supply him with the real goods and services that he wants in exchange for his money. But, from the standpoint of the national economy as a whole, money is not wealth. It is just a way to transfer wealth or to give people incentives to produce wealth.

Even in peacetime, governments have found many things to spend money on, including luxurious living by kings or dictators and numerous showy projects that have been common with both democratic and undemocratic governments. To pay for such things, using the government’s power to create more money has often been considered easier than raising tax rates. Put differently, inflation is in effect a hidden tax. The money that people have saved is robbed of part of its purchasing power, which is quietly transferred to the government that issues new money.

Because of the powerful leverage of the Federal Reserve System, public statements by the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board are scrutinized by bankers and investors for clues as to whether ”the Fed” is likely to tighten the money supply or ease up. An unguarded statement by the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, or a statement that is misconstrued by financiers, can set off a panic in Wall Street that causes stock prices to plummet. Or, if the Federal Reserve Board chairman sounds upbeat, stock prices may soar. Given such drastic repercussions, which can affect financial markets around the world, Federal Reserve Board chairmen over the years have learned to speak in highly guarded and Delphic terms that leave listeners puzzled as to what they really mean.

No one has to stand over an American farmer and tell him to take the rotten peaches out of a basket before they spoil the others, because these peaches are his private property and he is not about to lose money if he doesn’t have to. Property rights create self-monitoring, which tends to be both more effective and less costly than third-party monitoring.

The only animals threatened with extinction are animals not owned by anybody. Colonel Sanders is not about to let chickens become extinct. Nor will McDonald’s stand idly by and let cows become extinct. It is things not owned by anybody (air and water, for example) which are polluted. In centuries past, sheep were allowed to graze on unowned land -”the commons,” as it was called-with the net result that land on the commons was so heavily grazed that it had little left but patchy ground and the shepherds had hungry and scrawny sheep. But privately owned land adjacent to the common was usually in far better condition.

While central planning has an unimpressive record in industry as well, the fact that its agricultural failures are usually far worse, and more often catastrophic, suggests the crucial role of knowledge. Industrial products and industrial production processes have a far greater degree of uniformity than is found in agriculture. Orders from Moscow on how to make steel in Vladivostok have more chances of achieving their goal than orders from Moscow on how to grow carrots or strawberries in Vladivostok.

By collectivizing this decision and having it made by government, an end result can be achieved that is more in keeping with what most people want than if those people were allowed to decide individually what to do. Even the strongest defenders of the free market do not suggest that each individual should buy military defense in the marketplace. In short, there are things that government can do more efficiently than individuals because external costs or external benefits make individual decisions, based on individual interests, a less effective way of weighing costs and benefits to the whole society.

Setting standards is another government function which falls into this category. For centuries governments have set standards of measurement or prescribed certain measurements, such as the width of rails on railroads. The inch, the yard, and the mile are all government-prescribed units of measurement, as are pints, quarts, and gallons. If individuals had each set up their own units of measurement, transactions and contracts would be a nightmare of complications, as would the legal enforcement process.

The same principle applies in many other contexts, where minute traces of impurities can produce major political and legal battles-and consume millions of tax dollars with little or no net effect on the health or safety of the public. One legal battle raged for a decade over the impurities in a New Hampshire toxic waste site, where these wastes were so diluted that children could have eaten some of the dirt there for 70 days a year without any significant harm-if there had been any children playing there, which there were not. As a result of spending more than $9 million, the level of impurities was reduced to the point where children could have eaten the dirt there 245 days a year.

Because a national economy includes such a huge mixture of ever-changing goods and services, merely measuring the rate of inflation is much more chancy than confident discussions of statistics on the subject might indicate. As already noted, cars and houses have changed dramatically over the years. If the average car today costs X percent more than it used to, does that mean that there has been X percent inflation or that most of that change has represented higher prices paid for higher quality? No one calls it inflation when someone who has been buying Chevrolets begins to buy Cadillacs and pays more money. Why then call it inflation when a Chevrolet begins to have features that were once reserved for Cadillacs and its costs rise to levels once charged for Cadillacs.

There is no fixed number of jobs that the two countries must fight over. If they both become more prosperous, they are both likely to create more jobs. The only question is whether international trade tends to make both countries more prosperous. As with any other exchange, the only reason international trade takes place in the first place is because both parties expect to benefit. If either side discovers that it is worse off, then it stops trading.

To illustrate what is meant by comparative advantage, suppose that one country is so efficient that it is capable of producing anything more cheaply than another country. Should the two countries trade?

Yes.

Why? Because, even in an extreme case where one country can produce anything more cheaply than another country, it may do so to varying degrees. For example, it may be twice as efficient at producing chairs but ten times as efficient at producing television sets. In this case, the total number of chairs and television sets produced in the two countries combined would be greater if one country produced all the chairs and the other produced all the television sets. Then they could trade with one another and each end up with more chairs and more television sets than if they each produced both products for themselves.

In a prosperous country such as the United States, a fallacy that sounds very plausible is that American goods cannot compete with goods produced by low-wage workers in poorer countries. But, plausible as this may sound, both history and economics refute it. Historically, high-wage countries have been exporting to low-wage countries for centuries. Britain was the world’s greatest exporter in the nineteenth century and its wage rates were much higher than the wage rates in many, if not most, of the countries to which it sold.

Economically, the key flaw in the high-wage argument is that it confuses wage rates with labor costs-and labor costs with total costs.

When workers in a prosperous country receive twice the wage rate as workers in a poorer country and produce three times the output per man-hour, then it is the high-wage country which has the lower labor costs. That is, it is cheaper to get a given amount of work done in the more prosperous country simply because it takes less labor, even though individual workers are paid more.

The higher-paid workers may be more efficiently organized and managed, or have far more or better machinery to work with. There are, after all, reasons why one country is more prosperous than another and often that reason is that they are more efficient at producing output.

Foreigners invested $12 billion in American businesses in 1980 and this rose over the years until they were investing more than $200 billion annually by 1998. Looked at in terms of things, there is nothing wrong with this. It creates more jobs for American workers and creates more goods for American consumers. Looked at in terms of words, however, this is a growing debt to foreigners.

Every time you deposit a hundred dollars in a bank, that bank goes a hundred dollars deeper in debt, because it is still your money and they owe it to you.

Some people might become alarmed if they were told that the bank in which they keep their life’s savings was going deeper and deeper into debt every year. But such worries would be completely uncalled for, since the bank’s growing debt means only that many other people are also depositing money in that same bank. Alarmists are unlikely to try to scare people by saying that American banks are going deeper into debt, because the banks themselves would correct the misconception and discredit the alarmists.

In short, countries with inefficient economies and corrupt governments are far more likely to receive foreign aid than to receive investments from people who are risking their own money. Put differently, the availability of foreign aid reduces the necessity for a country to restrict its investments to economically viable projects or to reduce its level of corruption.

One of those alternative uses is saving other human lives in other ways. Few things have saved as many lives as the simple growth of wealth. An earthquake powerful enough to kill a dozen people in California will kill hundreds of people in some less affluent country and thousands in a Third World nation.

Greater wealth enables California buildings, bridges, and other structures to be built to withstand far greater stresses than similar structures can withstand in poorer countries. Those injured in an earthquake in California can be rushed more quickly to far more elaborately equipped hospitals with larger numbers of more highly trained medical personnel.

Anyone who has driven in most big cities will undoubtedly feel that there is an unmet need for more parking spaces. But, while it is both economically and technologically possible to build cities in such a way as to have a parking space available for anyone who wants one, anywhere in the city at any hour or the day or night, does it follow that we should do it?

The cost of building vast new underground parking garages, or of tearing down existing buildings to create parking garages above ground, or of designing new cities with fewer buildings and more parking lots, would all be astronomical. What other things are we prepared to give up, in order to have this automotive heaven? Fewer hospitals? Less police protection? Fewer fire departments?

So long as we respond gullibly to political rhetoric about unmet needs, we will arbitrarily choose to shift resources to whatever the featured unmet need of the day happens to be and away from other things. Then, when another politician-or perhaps even the same politician at a later time-discovers that robbing Peter to pay Paul has left Paul worse off, and wants to help him meet his unmet needs, we will start shifting resources in another direction. In short, we will be like a dog chasing his tail and getting no closer, no matter how fast he runs. This is not to say that we have the ideal trade-offs already and should leave them alone. Rather, it says that whatever trade-offs we make should be seen from the outset as trade-offs-not meeting unmet needs.

Similarly, someone who wins an automobile with a $20 lottery ticket can end up with the same car for which someone else paid $20,000. But one bought a low probability of getting a car and the other bought a virtual certainty. The car they ended up with may be the same but what they bought was not the same.

The Post Office has run a massive advertising campaign claiming that its two-day delivery service, Priority Mail, costs much less than the competing two-day delivery services of Federal Express or United Parcel Service. The only problem with this claim is that almost all Federal Express or UPS two-day packages actually get delivered in two days, while little more than one third of the long-distance Priority Mail arrives in two days. In other words, the more expensive service is more reliable, which was why it is more expensive. The Post Office ads were comparing apples and oranges.

Since brand names are a substitute for specific knowledge, how valuable they are depends on how much knowledge you already have about the particular product or service.

But, when film is sold with brand names on the boxes, Kodak knows that it will lose millions of dollars in sales if it falls behind Fuji in quality and Fuji knows that it will lose millions if it falls behind Kodak.

But, if everybody is greedy, then the word is virtually meaningless. If it refers to people who desire far more money than most others would aspire to, then the history of most great American fortunes-Ford, Rockefeller, Carnegie, etc.-suggests that the way to amass vast amounts of wealth is to figure out some way to provide goods and services at lower prices, not higher prices.

One of the popular fallacies that has become part of the tradition of anti-trust law is ”predatory pricing.’’ According to this theory, a big company that is out to eliminate its smaller competitors and take over their share of the market will lower its prices to a level that dooms the competitor to unsustainable losses and forces it out of business. Then, having acquired a monopolistic position, it will raise its prices-not just to the previous level, but to new and higher levels in keeping with its new monopolistic position. Thus, it recoups its losses and enjoys above-normal profits thereafter, at the expense of the consumers.

One of the most remarkable things about this theory is that those who advocate it seldom provide concrete examples of when it actually happened. Perhaps even more remarkable, they have not had to do so, even in courts of law, in anti-trust cases.

At various times it has been thought that people who save are depriving the economy of purchasing power and thus endangering other people’s jobs. But money that is saved does not vanish into thin air. It is lent out by banks and other financial institutions, being spent by different people for different purposes, but still remaining just as much a part of purchasing power as if it had never been saved.

In the crudest form of the purchasing power fallacy, the enormous increase in output resulting from the industrial revolution led many in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to wonder how the economy could possibly absorb such unprecedentedly large and growing production. What would happen when all the needs of human beings had been met, as seemed imminent to some at the time, and the machines and workers kept producing more?

As history unfolded, this proved to be one of many non-problems with which imaginative members of the intelligentsia have managed to torture themselves, and alarm others, over the centuries. (Declining IQs, exhaustion of natural resources, overpopulation, and global warming are others) The sating of human desires, which some feared in the early nineteenth century, still seems remote today, even though we have an abundance of such things as refrigerators, computers, and television sets that were not even dreamed of then.

What a group of French economists known as Physiocrats showed in the late eighteenth century was that the production of goods and services automatically generates the purchasing power needed to buy those goods and services. When the economy creates another hundred million dollars worth of output, that is also another hundred million dollars worth of wealth that can be used to buy this or other output. Production is ultimately bought with other production, using money as a convenience to facilitate the transactions.

In whatever activities they engage, non-profit organizations are not under the same pressures to get “the most bang for the buck” as are enterprises in which profit and loss determine their survival. This effects efficiency, not only in the narrow financial sense, but also in the broader sense of achieving avowed purposes. Colleges and universities, for example, can become disseminators of particular ideological views that happen to be in vogue (“political correctness”) and restrictors of alternative views, even though the goals of education would be better served by exposing students to contrasting and contending ideas.

By this time, you may no longer be as ready to believe those who talk about things selling ”below their real value” or about how terrible it is for the United States to be ”a debtor nation.” In the course of reading this book, you may have acquired a certain skepticism about government programs to make this or that ”affordable.” Statements and statistics about ”the rich” and ”the poor” may not be unthinkingly accepted any more. Nor should you find it mysterious that so many places with rent control laws also have housing shortages.